By Thomas Davis, DNAP, MAE, CRNA

Follow @procrnatom on twitter

Communicate, communicate, communicate…a message that has been drilled into all of us as a key ingredient for effective leadership, patient safety, teamwork, and the future of mankind. Collaborative teamwork requires that the vision of the leader be understood by the team and empowered workers deserve to know exactly what is expected of them. Partial or ineffective communication sets the stage for disaster regardless of knowledge or level of experience of those involved, as evidenced by the greatest loss of life in aviation history.

On a foggy morning in 1977 on the island of Tenerife, just off the coast of western Africa, KLM flight 4805 was awaiting clearance for takeoff as PanAm flight 1736, still on the runway, was rolling toward the nearest exit point. Pilots in each plane and the controller in the tower were all speaking in English, a learned second language for each person. Fog prevented visual contact from the tower to the runway so verbal talk in a non-native language via a radio was the only way to communicate the positions of the planes. Interpreting a message from the tower as clearance for takeoff, the KLM flight went to full throttle, accelerated, and hit the PanAm plane killing 583 people. Communication failure cost many innocent lives that day on what was otherwise a beautiful vacation island.

Communication is equally important for safety in healthcare. The Institute of Medicine published a report in 1999 stating that up to 100,000 deaths occur annually in the United States due to medical error. Current statistics published by the CDC and CMS indicate that death due to medical error has not been reduced in the past 20 years and root cause analysis of closed claims prompted the Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation to list communication errors as a major risk for patient safety. Poor communication in healthcare does not leave hundreds of people dead on a runway; however, the results are equally devastating to the family and friends of the injured person. Just as in aviation, effective communication among healthcare providers prevents errors and saves lives.

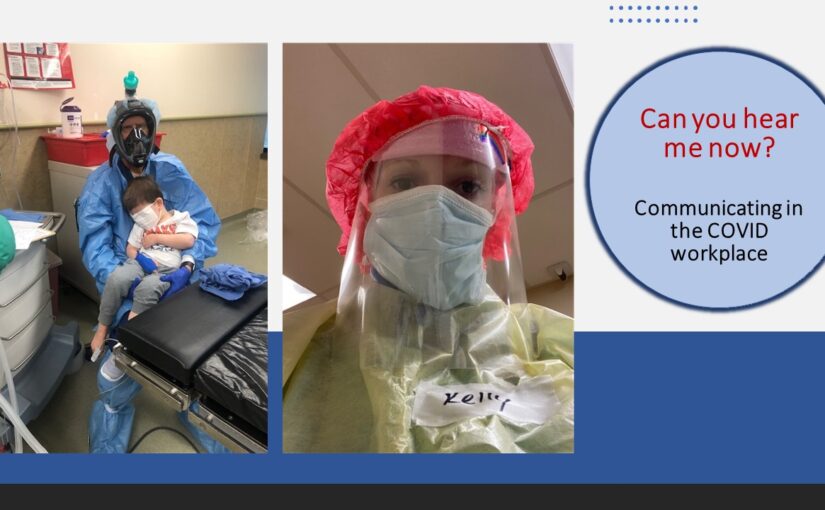

Shrouding the body in plastic, masking the face, and shielding the head stops more than the COVID virus, it muffles sound and removes visual ques.

The threat of the COVID 19 virus mandates that healthcare providers utilize personal protective equipment (PPE) for their own security as well as the safety of friends and family that they interact with after work. Along with the protection provided by the PPE barrier comes the unintended threat of patient harm caused by difficult communication among those wearing full PPE. For example, recently a surgical technician in our break room commented, “I’m glad I know his routine because I didn’t understand half of what he said to me.” My personal experience while wearing PPE is that I find myself speaking louder, standing closer and asking people to repeat themselves frequently. The option of being like the KLM pilot and acting based on what was thought to have been said rather than seeking clarification is not acceptable in healthcare.

An internet search related to communicating while wearing PPE revealed the story of a nurse who was hard of hearing, dependent upon lip reading and was forced to retire when masks became a requirement in her workplace. No doubt, many of our elderly patients, with or without COVID, share her inability to fully understand words spoken through a mask and face shield. Even when word are heard and understood, masks present a barrier to developing trusting relationships with patients as evidenced by a study by Wong et al (2013) published in the BMC Family Practice journal. The study revealed that family practice physicians who wore a mask while interviewing patients were less likely to create an empathetic, trusting relationship. The findings reinforce the importance of removing the facemask if possible when around non-COVID patients while maintaining strict social distance rules.

Am I suggesting that we should NOT be using PPE? Emphatically NO because PPE is crucial for provider safety; however, we must take steps to ensure that PPE is not a barrier to collaborating with colleagues or connecting with patients. Here are some tips for effective communication while wearing protective equipment.

Communicate clearly in the COVID workplace

Use closed loop communication. Advocating for patient safety, the CDC recommends closed loop communication while wearing PPE to ensure understanding. With closed loop communication, the sender initiates the message, the receiver acknowledges the message by giving feedback, and the sender verifies the feedback. For example, one person may ask another to draw up 0.5 mg of atropine. The second person repeats, “I will draw up 0.5 mg of atropine” to which the sender says, “yes, 0.5 mg of atropine is correct.”

Use technology. We live in a digital world and technology abounds to assist communication. When words are muffled, mobile devices can be used for typing and sending messages to others while wearing PPE. Always protect devices in a plastic wrap and wipe them frequently with disinfectant. In addition to personal devices, walkie-talkie type gadgets can be worn under the PPE garment and provide a channel for clear communication. The Vocera system is but one example of an electronic device designed to provide effective communication while wearing PPE.

Create trigger words and signs. Pre-arrange both verbal and non-verbal ways to bring the team to a halt if something is not understood or is not correct. Make a large sign that says “STOP” or have a red card to hold up for all to see when immediate help is needed. Agree on a hand gesture such as the “timeout” signal given by a football referee or the “halt” sign given by a police officer to stop any procedure that you feel is unsafe. Next, consider other supplies that are needed or events that happen frequently where a sign would be appropriate for informing colleagues. Make sure that signs are appropriately cleaned between uses.

Use body language and facial expressions. Writing in Health News Hub, author Ken Harrison offers advice for using the body to enhance communication while wearing PPE. Recommendations include maintaining a relaxed posture and using hands and arms to reinforce the words that are spoken. Stand where you can see one another’s facial expressions. Psychology Today author Karen Krauss Whitbourne notes that the eyes tell the story when it is difficult to hear words. Joy, fear, anxiety, and excitement are all expressed through the eyes and eyebrows add emphasis. Use them to your advantage when your words are difficult to understand.

Gestures and nods. Several years ago, I was told that traveling in Italy is easy because Italians talk with their hands; just ask for directions and watch their hands. When in PPE, do as the Romans and use your hands to reinforce your words. If you need two syringes, hold up two fingers. When a patient needs to move to a new position, use your hands to indicate what you want the patient or your assistant to do. While talking to another person, use head nods to indicate understanding of what was said.

Flash cards and pictures. Being sick, fearing death, and receiving treatment from people in space suits can be very frightening. Take and print a picture of yourself, wrap it in plastic and pin it to the outside of your gown to let patients know that there is a human inside. Create flash cards for instructions that are frequently given to patients and hold them up as you talk to the patient. As above, use your eyes, gestures, and body language to reinforce the message you are sending.

The COVID crisis has caused healthcare workers to pause and re-define their workflow to ensure that patients receive effective treatment while solidifying the safety of providers. The first step toward safety is to become aware that others may not understand what you say, and the second step is to immediately halt the other person and ask for clarification if you do not understand them. With some thought and pre-planning, the barriers put in place to protect providers need not pose a threat to those in need of their care. Rather than behaving like the pilot sitting on a foggy runway and taking action based on a garbled message, use all your resources to creatively ensure that messages are accurately sent and received. Who knows, learning to speak loudly while using facial expressions and hand gestures might position you for a career on stage when theaters reopen.

Tom is a published author, skilled anesthetist, proven leader, and frequently requested speaker. Click here to view current topics ready for presentation.